Public employees in West Virginia who took the drugs lost weight and were healthier, and some are despondent that the state is canceling a program to help pay for them.

Tag: North Carolina

Jóvenes latinos gay ven un porcentaje cada vez mayor de nuevos casos de VIH; piden financiación específica

Charlotte, Carolina del Norte. — Cuatro meses después de buscar asilo en Estados Unidos, Fernando Hermida comenzó a toser y a sentirse cansado. Primero pensó que estaba resfriado. Luego aparecieron llagas en su ingle y empezó a empapar su cama de sudor. Se hizo una prueba.

El día de Año Nuevo de 2022, a los 31 años, supo que tenía VIH.

“Pensé que me iba a morir”, dijo, recordando el escalofrío que le recorrió el cuerpo cuando revisaba sus resultados. Luchó por navegar un nuevo y complicado sistema de atención médica. A través de una organización de VIH que encontró en internet, recibió una lista de proveedores médicos en Washington, DC, donde estaba en ese momento. Pero no le devolvieron las llamadas durante semanas.

Hermida, que solo habla español, no sabía a dónde ir.

Para cuando Hermida recibió su diagnóstico, el Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos de Estados Unidos (HHS) llevaba adelante desde hacía unos tres años una iniciativa federal para acabar con la epidemia de VIH en la nación, invirtiendo cada año cientos de millones de dólares en ciertos estados, condados y territorios con las tasas de infección más altas.

El objetivo era llegar a las aproximadamente 1.2 millones de personas que viven con VIH, incluidas algunas que ni siquiera lo saben.

En general, las tasas estimadas de nuevas infecciones por VIH han disminuido un 23% desde 2012 hasta 2022. Pero un análisis de KFF Health News y Associated Press comprobó que la tasa no ha bajado para los latinos (que pueden ser de cualquier raza) tanto como para otros grupos raciales y étnicos.

Si bien en general los afroamericanos continúan teniendo las tasas más altas de VIH en el país, los latinos representaron la mayor parte de los nuevos diagnósticos e infecciones de VIH entre hombres gays y bisexuales en 2022, según los datos disponibles más recientes, en comparación con otros grupos raciales y étnicos.

Los latinos, que constituyen aproximadamente el 19% de la población de Estados Unidos, representaron alrededor del 33% de las nuevas infecciones por VIH, según los Centros para el Control y Prevención de Enfermedades (CDC). El análisis halló que los latinos están experimentando un número desproporcionado de nuevas infecciones y diagnósticos en todo el país, con las tasas de diagnóstico más altas en el sureste.

Oficiales de salud pública en el condado de Mecklenburg, en Carolina del Norte, y el condado de Shelby, en Tennessee, donde los datos muestran que las tasas de diagnóstico han aumentado entre los latinos, dijeron a KFF Health News y AP que no tienen planes específicos para abordar el problema del VIH en esta población, o que éstos aún no se han finalizado.

Incluso en lugares con buena cantidad de recursos como San Francisco, en California, las tasas de diagnóstico de VIH aumentaron entre los latinos en los últimos años mientras disminuían entre otros grupos raciales y étnicos, a pesar de los objetivos del condado de reducir las infecciones entre los latinos.

“Las disparidades de VIH no son inevitables”, dijo en un comunicado Robyn Neblett Fanfair, directora de la División de Prevención del VIH de los CDC. Señaló las inequidades sistémicas, culturales y económicas, como el racismo, las diferencias de idioma y la desconfianza en los médicos.

Y aunque los CDC proporcionan algunos fondos para grupos minoritarios, defensores de las políticas de salud para los latinos quieren que el HHS declare una emergencia de salud pública con la esperanza de dirigir más dinero a las comunidades latinas, argumentando que los esfuerzos actuales no son suficientes.

“Nuestra invisibilidad ya no es tolerable”, dijo Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, co-presidente del Consejo Asesor Presidencial sobre VIH/SIDA.

Perdido sin un intérprete

Hermida sospecha que contrajo el virus mientras estaba en una relación abierta con un compañero masculino antes de llegar a Estados Unidos. A fines de enero de 2022, meses después que comenzaran sus síntomas, fue a una clínica en la ciudad de Nueva York que un amigo lo ayudó a encontrar para finalmente recibir tratamiento para el VIH.

Demasiado enfermo para cuidarse solo, Hermida finalmente se mudó a Charlotte, Carolina del Norte, para estar más cerca de su familia y con la esperanza de recibir atención médica más constante. Se inscribió en una clínica de Amity Medical Group que recibe fondos del Programa Ryan White de VIH/SIDA, un plan de la red de seguridad federal que atiende a más de la mitad de los diagnosticados con VIH en la nación, independientemente de su estatus migratorio.

Después que se conectó con gestores de casos, su VIH se volvió indetectable. Pero dijo que, con el tiempo, la comunicación con la clínica se volvió menos frecuente y no recibía ayuda regular de un intérprete durante las visitas con su médico, que hablaba inglés.

Un representante de Amity confirmó que Hermida fue cliente, pero no respondió preguntas sobre su experiencia en la clínica.

Hermida dijo que tuvo dificultades para completar el papeleo para mantenerse inscrito en el programa Ryan White, y cuando su elegibilidad expiró, en septiembre de 2023, no pudo obtener su medicación.

Dejó la clínica y se inscribió en un plan de salud a través del mercado de seguros de la Ley de Cuidado de Salud a Bajo Precio (ACA). Pero Hermida no se dio cuenta que la aseguradora le exigía pagar una parte de su tratamiento para el VIH.

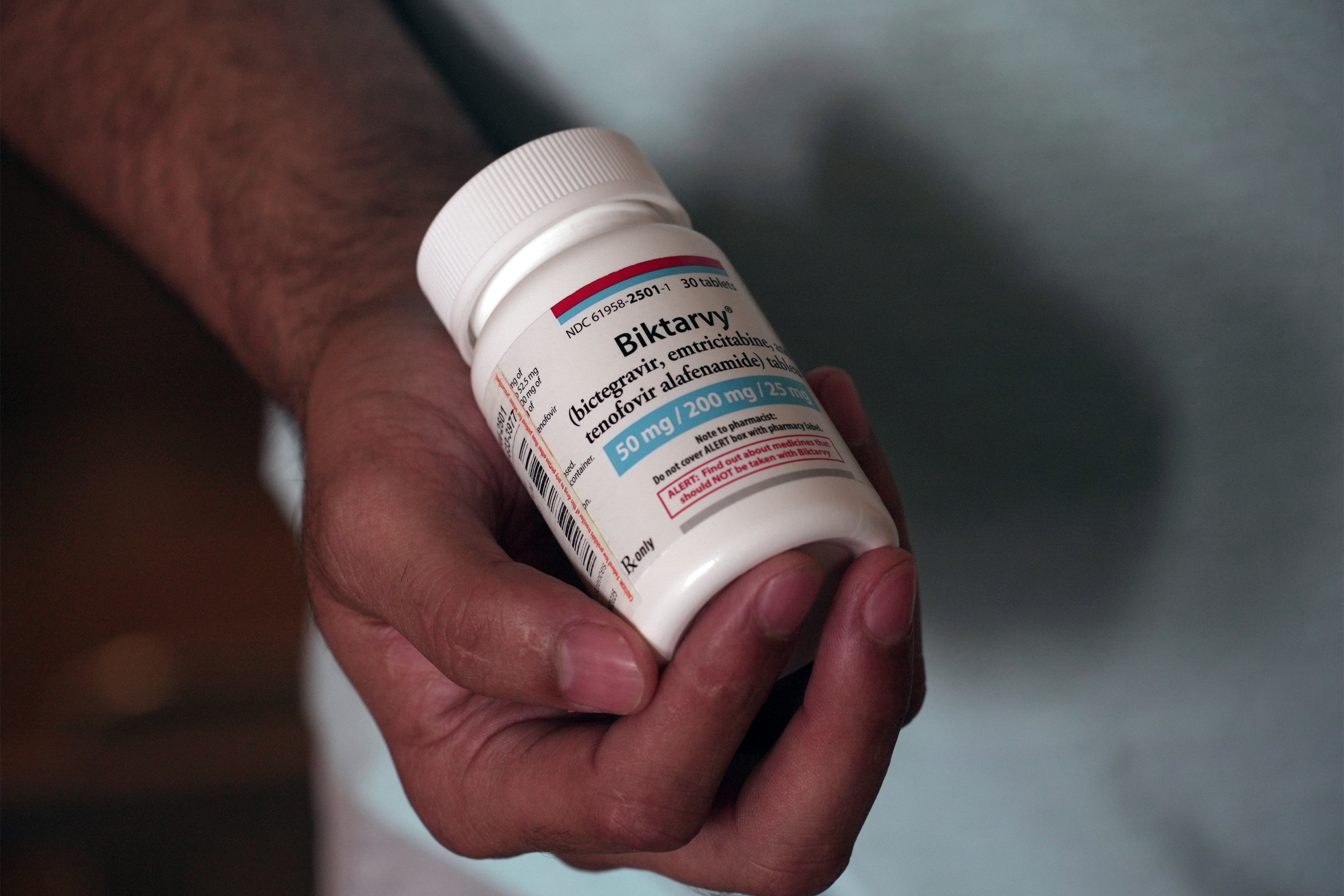

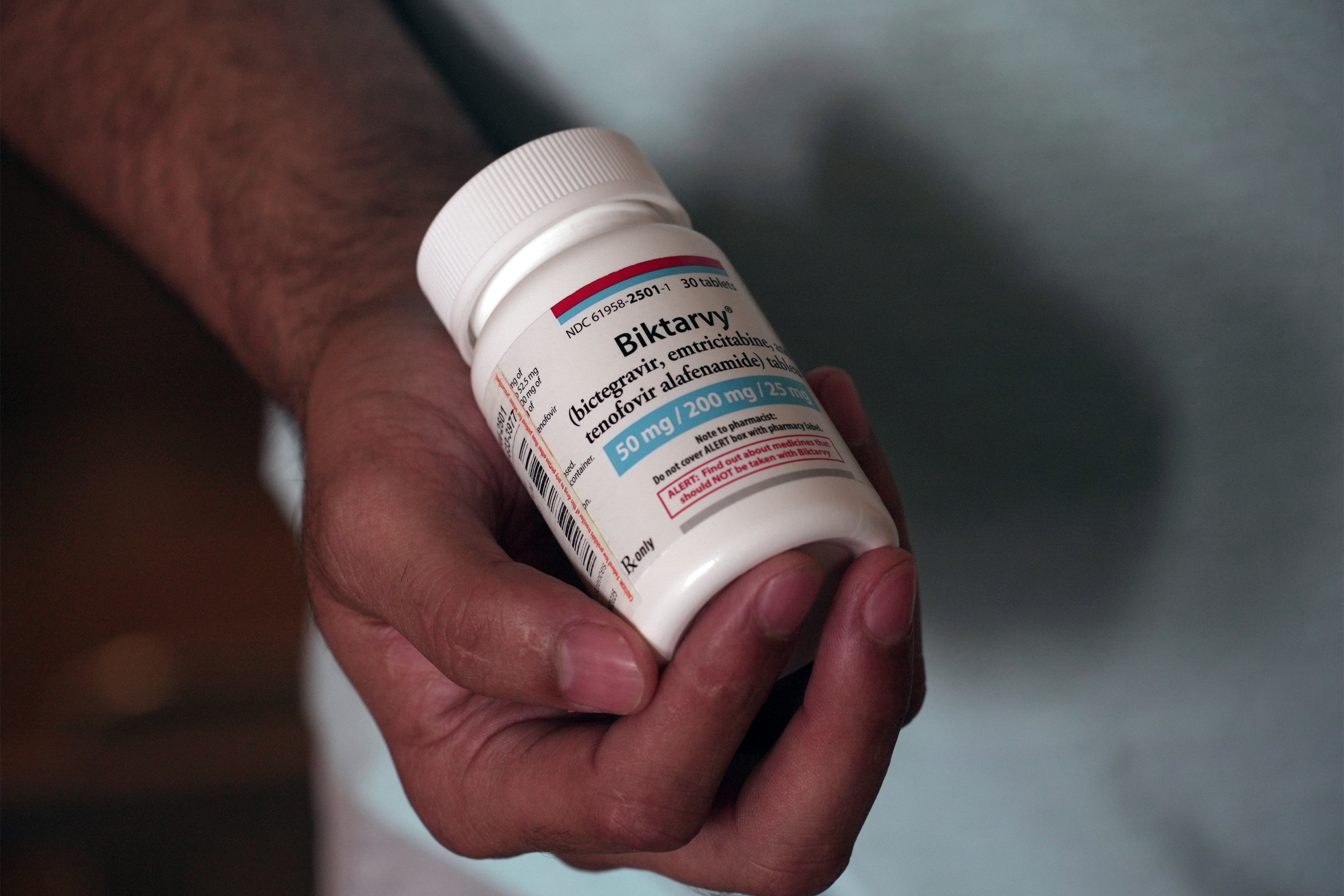

En enero, el conductor de Lyft recibió una factura de $1,275 por su antirretroviral, el equivalente a 120 viajes, dijo. Pagó la factura con un cupón que encontró en línea. En abril, recibió una segunda cuenta que no pudo pagar. Durante dos semanas, dejó de tomar la medicación que mantiene al virus indetectable, y por ende no transmisible.

“Estoy que colapso”, dijo. “Tengo que vivir para pagar la medicación”. Una forma de prevenir el VIH es la profilaxis previa a la exposición, o PrEP, que se toma regularmente para reducir el riesgo de contraer el VIH a través del sexo o el uso de drogas intravenosas. Fue aprobada por el gobierno federal en 2012, pero la adopción no ha sido uniforme entre los diferentes grupos raciales y étnicos: los datos de los CDC muestran tasas de cobertura de PrEP mucho más bajas entre los latinos que entre los estadounidenses blancos no hispanos.

Los epidemiólogos dicen que el buen uso de PrEP y el acceso constante al tratamiento son necesarios para construir resistencia a nivel comunitario.

Carlos Saldana, especialista en enfermedades infecciosas y ex asesor médico del Departamento de Salud de Georgia, ayudó a identificar cinco grupos de transmisión rápida de VIH que involucró a unos 40 latinos gay y hombres que tienen sexo con hombres desde febrero de 2021 hasta junio de 2022. Muchas personas en el grupo dijeron a los investigadores que no habían tomado PrEP y que les resultaba difícil entender el sistema de salud.

Saldana dijo que también experimentaron otras barreras, incluida la falta de transporte y el miedo a la deportación si buscaban tratamiento.

Defensores de políticas de salud para los latinos quieren que el gobierno federal redistribuya los fondos para la prevención del VIH, incluyendo pruebas y acceso a PrEP. De los casi $30 mil millones en dinero federal que se destinaron a servicios de atención médica para el VIH, tratamiento y prevención en 2022, solo el 4% se dirigió a la prevención, según un análisis de KFF.

Los defensores sugieren que más dinero podría ayudar a llegar a las comunidades latinas a través de esfuerzos como la divulgación basada en la fe en iglesias, pruebas en clubes durante fiestas latinas, y en capacitar a personal bilingüe para que realice las pruebas.

Aumentan las tasas latinas

El Congreso ha asignado $2.3 mil millones a lo largo de cinco años para la iniciativa Ending the HIV Epidemic, y las jurisdicciones que reciben el dinero deben invertir el 25% en organizaciones comunitarias.

Pero esta iniciativa no requiere dirigirse a determinados grupos, incluidos los latinos: delega en las ciudades, condados y estados la tarea de idear estrategias específicas.

En 34 de las 57 áreas que reciben dinero, los casos van en la dirección equivocada: las tasas de diagnóstico entre los latinos aumentaron de 2019 a 2022 mientras que disminuían en otros grupos raciales y étnicos, halló el análisis de KFF Health News-AP.

A partir del 1 de agosto, los departamentos de salud estatales y locales deberán presentar informes anuales de gastos sobre el financiamiento en lugares que representan el 30% o más de los diagnósticos de VIH, dijeron los CDC. Antes, solo se requería esto en un pequeño número de estados.

En algunos estados y condados, el financiamiento de la iniciativa no ha sido suficiente para cubrir las necesidades de los latinos. Carolina del Sur, que vio las tasas entre latinos casi duplicarse de 2012 a 2022, no ha expandido las pruebas móviles de VIH en áreas rurales, donde la necesidad es alta entre los latinos, dijo Tony Price, gerente del programa de VIH en el departamento de salud del estado.

Carolina del Sur solo puede pagar a cuatro trabajadores comunitarios de salud enfocados en la divulgación sobre el VIH, y no todos son bilingües.

En el condado de Shelby, Tennessee, hogar de Memphis, la tasa de diagnóstico de VIH entre los latinos aumentó un 86% de 2012 a 2022. El Departamento de Salud dijo que recibió $2 millones en financiamiento de la iniciativa en 2023 y, aunque el plan del condado reconoce que los latinos son un grupo objeto, la directora del departamento, Michelle Taylor, dijo: “No hay campañas específicas solo entre los latinos”.

Hasta ahora, el condado de Mecklenburg, en Carolina del Norte, no incluyó objetivos específicos para abordar el VIH en la población latina, donde las tasas de nuevos diagnósticos se han más que duplicado en una década, pero disminuyeron ligeramente entre otros grupos raciales y étnicos.

El departamento de salud ha utilizado fondos para campañas de marketing bilingües y concientización sobre la PrEP.

Mudarse por la medicina

Cuando llegó el momento para Hermida de empacar y mudarse a la tercera ciudad en dos años, su prometido, que está tomando PrEP, sugirió buscar atención en Orlando, Florida.

La pareja, que eran amigos en la escuela secundaria en Venezuela, tenía algunos familiares y amigos en Florida, y habían escuchado sobre Pineapple Healthcare, una clínica de atención primaria sin fines de lucro dedicada a apoyar a los latinos que viven con VIH.

La clínica está en un consultorio al sur del centro de Orlando. El personal, mayoritariamente latino, viste camisetas turquesa con estampado de piñas, y se escucha con más frecuencia español que inglés en los cuartos de atención y en los pasillos.

“En su esencia, si la organización no es dirigida por y para personas de color, entonces solo somos una idea de último momento”, dijo Andres Acosta Ardila, director de divulgación comunitaria en Pineapple Healthcare, quien fue diagnosticado con VIH en 2013.

“¿Te mudaste reciente [mente], ya por fin?”, preguntó la enfermera Eliza Otero, quien comenzó a tratar a Hermida cuando todavía vivía en Charlotte. “Hace un mes desde la última vez que nos vimos”.

Todavía necesitan trabajar en bajar su colesterol y presión arterial, le dijo. Aunque su carga viral sigue siendo alta, Otero dijo que debería mejorar con atención regular y constante.

Pineapple Healthcare, que no recibe dinero de la iniciativa federal, ofrece atención primaria completa principalmente a hombres latinos. Allí, Hermida obtiene su medicación para el VIH sin costo porque la clínica es parte de un programa federal de descuento de medicamentos.

En muchos sentidos, la clínica es un oasis. La tasa de nuevos diagnósticos para los latinos en el condado de Orange, Florida, que incluye Orlando, aumentó alrededor de un tercio desde 2012 hasta 2022, mientras que disminuyó un tercio para otros. Florida tiene la tercera población latina más grande de Estados Unidos y tuvo la séptima tasa más alta de nuevos diagnósticos de VIH entre latinos en la nación en 2022.

Hermida, que tiene pendiente su caso de asilo, nunca imaginó que obtener medicación sería tan difícil, dijo durante el viaje de 500 millas de Carolina del Norte a Florida. Después de habitaciones de hotel, trabajos perdidos y despedidas familiares, espera que su búsqueda de tratamiento consistente para el VIH, que ha definido su vida en los últimos dos años, finalmente pueda llegar a su fin.

“Soy un nómade a la fuerza, pero bueno, como dicen mi prometido y mis familiares, yo tengo que estar donde me den buenos servicios médicos”, dijo.

Esa es la prioridad ahora, agregó.

KFF Health News y The Associated Press analizaron datos de los Centros para el Control y Prevención de Enfermedades de Estado Unidos sobre el número de nuevos diagnósticos e infecciones de VIH entre estadounidenses de 13 años y más a nivel local, estatal y nacional.

Esta historia utiliza principalmente datos de tasas de incidencia —estimaciones de nuevas infecciones— a nivel nacional y datos de tasas de diagnóstico a nivel estatal y de condados.

Bose produjo esta historia desde Orlando, Florida. Reese, desde Sacramento, California. La periodista de video Laura Bargfeld colaboró con este informe.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department recibe apoyo de la Fundación Robert Wood Johnson. AP es responsable de todo el contenido.

Young Gay Latinos See Rising Share of New HIV Cases, Leading to Call for Targeted Funding

CHARLOTTE, N.C. — Four months after seeking asylum in the U.S., Fernando Hermida began coughing and feeling tired. He thought it was a cold. Then sores appeared in his groin and he would soak his bed with sweat. He took a test.

On New Year’s Day 2022, at age 31, Hermida learned he had HIV.

“I thought I was going to die,” he said, recalling how a chill washed over him as he reviewed his results. He struggled to navigate a new, convoluted health care system. Through an HIV organization he found online, he received a list of medical providers to call in Washington, D.C., where he was at the time, but they didn’t return his calls for weeks. Hermida, who speaks only Spanish, didn’t know where to turn.

By the time of Hermida’s diagnosis, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services was about three years into a federal initiative to end the nation’s HIV epidemic by pumping hundreds of millions of dollars annually into certain states, counties, and U.S. territories with the highest infection rates. The goal was to reach the estimated 1.2 million people living with HIV, including some who don’t know they have the disease.

Overall, estimated new HIV infection rates declined 23% from 2012 to 2022. But a KFF Health News-Associated Press analysis found the rate has not fallen for Latinos as much as it has for other racial and ethnic groups.

While African Americans continue to have the highest HIV rates in the United States overall, Latinos made up the largest share of new HIV diagnoses and infections among gay and bisexual men in 2022, per the most recent data available, compared with other racial and ethnic groups. Latinos, who make up about 19% of the U.S. population, accounted for about 33% of new HIV infections, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The analysis found Latinos are experiencing a disproportionate number of new infections and diagnoses across the U.S., with diagnosis rates highest in the Southeast. Public health officials in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, and Shelby County, Tennessee, where data shows diagnosis rates have gone up among Latinos, told KFF Health News and the AP that they either don’t have specific plans to address HIV in this population or that plans are still in the works. Even in well-resourced places like San Francisco, California, HIV diagnosis rates grew among Latinos in the last few years while falling among other racial and ethnic groups despite the county’s goals to reduce infections among Latinos.

“HIV disparities are not inevitable,” Robyn Neblett Fanfair, director of the CDC’s Division of HIV Prevention, said in a statement. She noted the systemic, cultural, and economic inequities — such as racism, language differences, and medical mistrust.

And though the CDC provides some funds for minority groups, Latino health policy advocates want HHS to declare a public health emergency in hopes of directing more money to Latino communities, saying current efforts aren’t enough.

“Our invisibility is no longer tolerable,” said Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, co-chair of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS.

Lost Without an Interpreter

Hermida suspects he contracted the virus while he was in an open relationship with a male partner before he came to the U.S. In late January 2022, months after his symptoms started, he went to a clinic in New York City that a friend had helped him find to finally get treatment for HIV.

Too sick to care for himself alone, Hermida eventually moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, to be closer to family and in hopes of receiving more consistent health care. He enrolled in an Amity Medical Group clinic that receives funding from the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, a federal safety-net plan that serves over half of those in the nation diagnosed with HIV, regardless of their citizenship status.

His HIV became undetectable after he was connected with case managers. But over time, communication with the clinic grew less frequent, he said, and he didn’t get regular interpretation help during visits with his English-speaking doctor. An Amity Medical Group representative confirmed Hermida was a client but didn’t answer questions about his experience at the clinic.

Hermida said he had a hard time filling out paperwork to stay enrolled in the Ryan White program, and when his eligibility expired in September 2023, he couldn’t get his medication.

He left the clinic and enrolled in a health plan through the Affordable Care Act marketplace. But Hermida didn’t realize the insurer required him to pay for a share of his HIV treatment.

In January, the Lyft driver received a $1,275 bill for his antiretroviral — the equivalent of 120 rides, he said. He paid the bill with a coupon he found online. In April, he got a second bill he couldn’t afford.

For two weeks, he stopped taking the medication that keeps the virus undetectable and intransmissible.

“Estoy que colapso,” he said. I’m falling apart. “Tengo que vivir para pagar la medicación.” I have to live to pay for my medication.

One way to prevent HIV is preexposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, which is regularly taken to reduce the risk of getting HIV through sex or intravenous drug use. It was approved by the federal government in 2012 but the uptake has not been even across racial and ethnic groups: CDC data show much lower rates of PrEP coverage among Latinos than among white Americans.

Epidemiologists say high PrEP use and consistent access to treatment are necessary to build community-level resistance.

Carlos Saldana, an infectious disease specialist and former medical adviser for Georgia’s health department, helped identify five clusters of rapid HIV transmission involving about 40 gay Latinos and men who have sex with men from February 2021 to June 2022. Many people in the cluster told researchers they had not taken PrEP and struggled to understand the health care system.

They experienced other barriers, too, Saldana said, including lack of transportation and fear of deportation if they sought treatment.

Latino health policy advocates want the federal government to redistribute funding for HIV prevention, including testing and access to PrEP. Of the nearly $30 billion in federal money that went toward things like HIV health care services, treatment, and prevention in 2022, only 4% went to prevention, according to a KFF analysis.

They suggest more money could help reach Latino communities through efforts like faith-based outreach at churches, testing at clubs on Latin nights, and training bilingual HIV testers.

Latino Rates Going Up

Congress has appropriated $2.3 billion over five years to the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative, and jurisdictions that get the money are to invest 25% of it in community-based organizations. But the initiative lacks requirements to target any particular groups, including Latinos, leaving it up to the cities, counties, and states to come up with specific strategies.

In 34 of the 57 areas getting the money, cases are going the wrong way: Diagnosis rates among Latinos increased from 2019 to 2022 while declining for other racial and ethnic groups, the KFF Health News-AP analysis found.

Starting Aug. 1, state and local health departments will have to provide annual spending reports on funding in places that account for 30% or more of HIV diagnoses, the CDC said. Previously, it had been required for only a small number of states.

In some states and counties, initiative funding has not been enough to cover the needs of Latinos.

South Carolina, which saw rates nearly double for Latinos from 2012 to 2022, hasn’t expanded HIV mobile testing in rural areas, where the need is high among Latinos, said Tony Price, HIV program manager in the state health department. South Carolina can pay for only four community health workers focused on HIV outreach — and not all of them are bilingual.

In Shelby County, Tennessee, home to Memphis, the Latino HIV diagnosis rate rose 86% from 2012 to 2022. The health department said it got $2 million in initiative funding in 2023 and while the county plan acknowledges that Latinos are a target group, department director Michelle Taylor said: “There are no specific campaigns just among Latino people.”

Up to now, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, didn’t include specific targets to address HIV in the Latino population — where rates of new diagnoses more than doubled in a decade but fell slightly among other racial and ethnic groups. The health department has used funding for bilingual marketing campaigns and awareness about PrEP.

Moving for Medicine

When it was time to pack up and move to Hermida’s third city in two years, his fiancé, who is taking PrEP, suggested seeking care in Orlando, Florida.

The couple, who were friends in high school in Venezuela, had some family and friends in Florida, and they had heard about Pineapple Healthcare, a nonprofit primary care clinic dedicated to supporting Latinos living with HIV.

The clinic is housed in a medical office south of downtown Orlando. Inside, the mostly Latino staff is dressed in pineapple-print turquoise shirts, and Spanish, not English, is most commonly heard in appointment rooms and hallways.

“At the core of it, if the organization is not led by and for people of color, then we’re just an afterthought,” said Andres Acosta Ardila, the community outreach director at Pineapple Healthcare, who was diagnosed with HIV in 2013.

“¿Te mudaste reciente, ya por fin?” asked nurse practitioner Eliza Otero. Did you finally move? She started treating Hermida while he still lived in Charlotte. “Hace un mes que no nos vemos.” It’s been a month since we last saw each other.

They still need to work on lowering his cholesterol and blood pressure, she told him. Though his viral load remains high, Otero said it should improve with regular, consistent care.

Pineapple Healthcare, which doesn’t receive initiative money, offers full-scope primary care to mostly Latino males. Hermida gets his HIV medication at no cost there because the clinic is part of a federal drug discount program.

The clinic is in many ways an oasis. The new diagnosis rate for Latinos in Orange County, Florida, which includes Orlando, rose by about a third from 2012 through 2022, while dropping by a third for others. Florida has the third-largest Latino population in the U.S., and had the seventh-highest rate of new HIV diagnoses among Latinos in the nation in 2022.

Hermida, whose asylum case is pending, never imagined getting medication would be so difficult, he said during the 500-mile drive from North Carolina to Florida. After hotel rooms, jobs lost, and family goodbyes, he is hopeful his search for consistent HIV treatment — which has come to define his life the past two years — can finally come to an end.

“Soy un nómada a la fuerza, pero bueno, como me comenta mi prometido y mis familiares, yo tengo que estar donde me den buenos servicios médicos,” he said. I’m forced to be a nomad, but like my family and my fiancé say, I have to be where I can get good medical services.

That’s the priority, he said. “Esa es la prioridad ahora.”

KFF Health News and The Associated Press analyzed data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the number of new HIV diagnoses and infections among Americans ages 13 and older at the local, state, and national levels. This story primarily uses incidence rate data — estimates of new infections — at the national level and diagnosis rate data at the state and county level.

Bose reported from Orlando, Florida. Reese reported from Sacramento, California. AP video journalist Laura Bargfeld contributed to this report.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is responsible for all content.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Bird Flu Outbreak in Cattle May Have Begun Months Earlier Than Thought

Buried in Wegovy Costs, North Carolina Will Stop Paying for Obesity Drugs

In North Carolina, More People Are Training to Support Patients Through an Abortion

Lauren Overman has a suggested shopping list for her clients preparing to get an abortion. The list includes a heating pad, a journal, aromatherapy oils — things that could bring physical or emotional comfort after the procedure.

Overman is an abortion doula.

She has worked as a professional birth doula for many years. Recently, Overman also began offering advice and emotional support to people as they navigate having an abortion, often a lonely time. She makes her services available either free or on a sliding scale to abortion patients. Other abortion doulas charge between $200 and $800.

Overman is one of around 40 practicing abortion doulas in North Carolina, according to an estimate from local abortion rights groups — a number that could soon grow. North Carolina groups that train doulas said they’ve seen an uptick in people wanting to become abortion doulas in the months since Roe v. Wade was overturned.

Every three months, the Carolina Abortion Fund offers free online classes for aspiring abortion doulas. Those sessions used to have 20 sign-ups at most, according to board member Kat Lewis. Now they have 40.

“It’s word of mouth. It’s people sharing ‘This is how I got through my abortion or miscarriage experience with the help of a doula.’ And someone being like, ‘That’s amazing. I need that. Or I wanna become that,’” Lewis said.

Demand for training has also surged at the Mountain Area Abortion Doula Collective in western North Carolina, which started in 2019. Ash Williams leads the free four-week doula training and includes talks on gender-inclusive language and the history of medical racism. The course also includes ways to support clients struggling with homelessness or domestic violence.

“The doula might be the only person that that person has told that they’re doing this. … That’s a big responsibility,” Williams said. “So we really want to approach our work with so much care.”

Going to the clinic and holding a patient’s hand during the procedure are among the services abortion doulas can offer, but some clinics don’t allow a support person in the room. So doulas like Overman find other ways to be supportive, such as sitting down with a woman afterward, to listen, share a meal, or just watch TV together.

It’s “holding space — being there so that they can bring something up if they want to talk about it. But also, there are no expectations that you have to talk about it if you don’t want to,” Overman said.

Overman uses Zoom to consult with people across the country, even in states where abortion is restricted or banned. She can help them locate the closest clinics or find transportation and lodging if they’re traveling a long distance.

Overman makes sure her clients know what to expect from the procedure, like how much bleeding is normal after either a surgical or medication abortion.

“You can fill up a super maxi pad in an hour. That’s OK,” she explained. “Fill up one or more pad every hour for two to three hours consecutively, then that’s a problem.”

Abortion doulas are not required to have medical training, and many do not. It’s not clear how many work across the U.S., because the job is not regulated.

There has been a jump in the number of people requesting her abortion doula services over the past several months, Overman said, from around four people a month to four every week.

If people are afraid to talk to their friends or relatives about an abortion, she said, sometimes the easiest thing to do is reach out to someone on the internet. A doula may start out as a stranger but can become a person who can be relied on for support.

This article is from a partnership that includes NPR, WFAE, and KHN.

Abortion Issue Helps Limit Democrats’ Losses in Midterms

Republicans are likely to take control of one or both houses of Congress when all the votes are counted, but Democrats on Wednesday were celebrating after their party defied expectations of substantial losses in the midterm election. The backlash over the Supreme Court’s decision in June to overturn 49 years of abortion rights was apparently a big reason.

Inflation and the economy proved the most important voting issue, cited as the motivation of 51% of voters in exit polls conducted by the Associated Press and analyzed by KFF pollsters. But abortion was the single-most important issue for a quarter of all voters, and for a third of women under age 50. Exit polls by NBC News placed the importance of abortion even higher, with 32% of voters saying inflation was their top voting issue and abortion ranking second at 27%.

The predicted “red wave” of Republicans toppling Democrats in the House and Senate did not happen, although as of Wednesday afternoon, it seemed likely that Republicans would gain the handful of seats they needed to take over the House majority.

In the Senate, where Republicans needed just one pickup to take control, no incumbent had officially lost, and Democrats captured the Pennsylvania seat being vacated by Republican Sen. Pat Toomey. Several other close races had yet to be called, and control of the chamber may well rest on a December runoff in Georgia between Democratic incumbent Sen. Raphael Warnock and Republican Herschel Walker. In recent decades, the party that controls the White House has generally suffered serious setbacks in congressional power in the midterms.

Among other issues facing voters Tuesday, residents of South Dakota approved an expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. That made it the seventh state to expand the program over the objections of a Republican governor and/or state legislature. Previous successful initiatives passed in Idaho, Maine, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Utah. South Dakota’s approval will reduce to 11 the number of states that have not expanded the program to people with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level, although included in that list are the heavily populated states of Texas, Florida, and Georgia.

On the issue of abortion rights, voters in five states across the political spectrum showed direct support through ballot initiatives. In the most closely watched of those measures, Michigan voters approved a constitutional amendment guaranteeing reproductive freedom, thus preventing a ban from 1931 from taking effect.

Kentucky voters narrowly rejected an amendment that would have declared in its constitution that there was no right to abortion. That made it the first Southern state to express direct support for abortion rights.

Other abortion rights ballot questions were approved in Vermont and California. The California measure, which passed with 65% of the vote, enshrined the rights to both abortion and contraception.

In Montana, a ballot measure to require that infants born alive after attempted abortions be given medical care was losing with 80% of the votes in. Such a requirement already exists in federal law.

In addition, in several key states where the legality of abortion hangs in the balance, governors and candidates who favor abortion rights defeated anti-abortion challengers, including Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan.

Abortion was also an issue in contested Supreme Court elections in at least six states, where challenges to abortion laws or constitutional interpretations could decide whether the procedure remains legal. One state saw party control of its high court flip: North Carolina, where a Republican challenger defeated a Democratic incumbent to give the GOP a 4-3 majority. Democratic judicial majorities appeared to be holding in Illinois and in Michigan, which holds nonpartisan judicial elections after the candidates are nominated by political parties. In Ohio, Republicans kept their majority on the high court.

In Kentucky, Justice Michelle Keller defeated challenger Joe Fischer, a Republican state legislator who sponsored Kentucky’s abortion trigger law. Montana incumbent Justice Ingrid Gustafson defeated her challenger, James Brown, a Republican endorsed by the state’s GOP governor and party leaders seeking to reverse a 1999 court ruling that the state constitution protects the right to an abortion.

Abortion was not the only health issue on state ballots Tuesday.

In Arizona, a ballot question to limit interest on medical debt won easily with 66% of the vote counted. In Oregon, however, a mostly unenforceable question declaring a “right to health care” in the state constitution was losing narrowly with 64% of the votes in.

California voters approved a ban on the sale of most flavored tobacco products while voters in Massachusetts supported dentists over insurance companies in approving a requirement that at least 83% of dental insurance premiums be spent on direct dental care. Massachusetts is the first state to impose such a requirement.

In Iowa, gun rights advocates scored a victory with easy passage of a constitutional amendment declaring that Iowans have “a fundamental individual right” to keep and bear arms, and that any restrictions on guns must stand up to “strict scrutiny” in court.

“Cuarto trimestre”: período clave para prevenir las muertes maternas

Durante varias semanas al año, el trabajo de la enfermera-comadrona Karen Sheffield-Abdullah es detectivesco. Con un equipo de investigadores médicos del Departamento de Salud Pública de Carolina del Norte examina los registros hospitalarios y los informes forenses de las madres que murieron después de dar a luz.

Estos comités de revisión de la mortalidad materna buscan pistas sobre lo que ha contribuido a estas muertes —recetas que nunca se recogieron, faltar a citas médicas postnatales, señales de alerta que los médicos pasaron por alto—, para averiguar cuántas podrían haberse evitado y cómo.

Los comités trabajan en 36 estados, y en la última y mayor recopilación de datos de este tipo, publicada en septiembre por los Centros para el Control y Prevención de Enfermedades (CDC), un sorprendente 84% de las muertes relacionadas con el embarazo se consideraron prevenibles.

Lo que resulta aún más alarmante para enfermeras-detectives como Sheffield-Abdullah es que el 53% de las muertes se produjeron mucho después de que las mujeres fueran dadas de alta del hospital, entre siete días y un año después del parto.

“Estamos muy centrados en el bebé”, afirma. “Una vez que el bebé está aquí, es casi como si la madre fuera descartada… Y en lo que realmente tenemos que pensar es en ese cuarto trimestre, ese tiempo después del nacimiento del bebé”.

Las condiciones de salud mental fueron la principal causa subyacente de muertes maternas entre 2017 y 2019. Las blancas no hispanas y las hispanas fueron las más propensas a morir por suicidio o sobredosis de drogas, mientras que los problemas cardíacos fueron la principal causa de muerte para las mujeres negras no hispanas.

Ambas circunstancias ocurren desproporcionadamente más tarde en el período posparto, según el informe de los CDC.

Los datos revelan múltiples deficiencias en el sistema de atención a las nuevas madres, desde los obstetras que no están adiestrados (o bien pagados) para buscar signos de problemas mentales o de adicción, hasta las pólizas que despojan a las mujeres de la cobertura médica poco después de dar a luz.

El principal problema es que el típico control postnatal de seis semanas es demasiado tarde, según Sheffield-Abdullah. En los datos de Carolina del Norte, las nuevas madres que murieron más tarde no acudieron a esta cita porque tenían que volver al trabajo o tenían otros niños pequeños, agregó.

“Tenemos que estar realmente en contacto mientras están en el hospital”, dijo Sheffield-Abdullah, y luego asegurarnos de que las pacientes reciban la atención de seguimiento adecuada “una o dos semanas después del parto”.

Otra de las recomendaciones de los CDC es más pruebas de detección de depresión y ansiedad posparto, durante todo el año posterior al parto, así como una mejor coordinación de la atención entre los servicios médicos y sociales, según David Goodman, que dirige el equipo de prevención de mortalidad materna de la División de Salud Reproductiva de los CDC, que publicó el informe.

Una crisis frecuente es que la adicción de uno de los padres se agrava tanto que los servicios de protección infantil se llevan al bebé, lo que precipita una sobredosis accidental o intencionada de la madre. Tener acceso al tratamiento y asegurarse de que las visitas a los niños se produzcan con regularidad podría ser la clave para prevenir estas muertes, apuntó Goodman.

El cambio político más importante ha sido la ampliación de la cobertura sanitaria gratuita a través de Medicaid, indicó. Hasta hace poco, la cobertura de Medicaid relacionada con el embarazo solía expirar dos meses después del parto, lo que obligaba a las mujeres a dejar de tomar medicamentos o de acudir a un terapeuta o a un médico porque no podían pagar el costo sin seguro médico.

Ahora, 36 estados han ampliado o tienen previsto ampliar la cobertura de Medicaid hasta un año completo después del parto, en parte como respuesta a los primeros trabajos de los comités de revisión de la mortalidad materna.

“Si esto no es una llamada a la acción, no sé qué es”, señaló Adrienne Griffen, directora ejecutiva de la Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance, una organización sin fines de lucro centrada en la política nacional. “Hace tiempo que sabemos que los problemas de salud mental son la complicación más común del embarazo y el parto. Solo que no hemos tenido la voluntad de hacer algo al respecto”.

El último estudio de los CDC de septiembre analizó 1,018 muertes en 36 estados, casi el doble de los 14 estados que participaron en el informe anterior. Los CDC están dando aún más fondos para las revisiones de la mortalidad materna, dijo Goodman, con la esperanza de captar datos más completos de más estados en el futuro.

El aumento de la concientización y la atención sobre la mortalidad materna les ha dado esperanza a activistas y médicos, especialmente por los esfuerzos para corregir las disparidades raciales: las mujeres negras tienen tres veces más probabilidades de morir por complicaciones relacionadas con el embarazo que las blancas.

Pero muchos de estos mismos partidarios de una mejor atención materna dicen estar consternados por la reciente decisión del Tribunal Supremo de Estados Unidos de erradicar el derecho federal al aborto; las restricciones en torno a la atención de la salud reproductiva, dicen, erosionarán los avances.

Desde que estados como Texas empezaron a prohibir los abortos en etapas tempranas del embarazo y a hacer menos excepciones para aquellos casos en los que la salud de la embarazada está en peligro, a algunas mujeres les resulta más difícil recibir atención de urgencia por un aborto espontáneo.

Los estados también están prohibiendo los abortos —incluso en casos de violación o incesto— en chicas jóvenes, que afrontan un riesgo mucho mayor de complicaciones o muerte por llevar un embarazo a término.

“Cada vez más el mensaje es que ‘no eres dueña de tu cuerpo’”, dijo Jameta Nicole Barlow, profesora adjunta de redacción, política y gestión sanitaria en la Universidad George Washington.

Según Barlow, esto no hará más que agravar los problemas de salud mental que experimentan las mujeres en torno al embarazo, especialmente las mujeres negras, que también se enfrentan a la larga historia intergeneracional de la esclavitud y el embarazo forzado. Sospecha que las cifras de mortalidad materna empeorarán antes de mejorar, debido a la interrelación entre la política y la psicología.

“Hasta que no abordemos lo que está ocurriendo políticamente”, dijo, “no vamos a poder ayudar a lo que está ocurriendo psicológicamente”.

Esta historia es parte de una alianza que incluye a KQED, NPR, y KHN.